Intro.

I’ll try not to get too nerdy about the metallurgy of what happens to steel for it to be transformed from soft steel into hard and brittle steel, however some technical detail needs to be covered for it to make sense to the novice knife-maker.

Quenching is the process of rapidly cooling down a certain type of steel so that it turns into a hard brittle steel known as either Austenite and Martensite. Once question that occasionally gets asked is “Can you harden any type of steel?” and the answer is no. Read on to find out more.

Consider this lot if you are thinking of making your own knives and more pertinent to this article quenching your own blades.

- Steel Composition

- Desired Hardness

- Critical Cooling Rate

- Minimizing Distortion and Cracking

- Preheating the Oil

- Uniform Heat Distribution

- Rapid Immersion

- Agitation

- Tempering

- Flammability

- Environmental Impact

- Cost

The Role of Quenching Oil.

No matter what solution you use, the whole idea is to remove heat from the steel as quickly as possible and as evenly as possible. If things are unstable in some way, perhaps the steel has different and uneven thicknesses. Perhaps it’s too thin or slightly too long for the forge for a successful heating up phase. If there is anything like this going on the steel may not get as hard and brittle as desired, they might even end up getting badly warped!

When the hobbyist knife-maker does all this there are so many things that may not be at the optimum preparation. So quenching may not always be successful. Knife making manufacturers on the other hand have perfected their processes and can usually create a the perfect environment for hardening and tempering their blades.

How many types of Quench Mediums are there?

Actually there are oodles of solutions to quench steel in, too many to mention here but here are the main ones you can try. It’s all based on what the elements are of that particular type of steel are and choosing the right quenchant to get the best out of your blade. A basic High Carbon steel for example has Carbon, Manganese, Phosphorus & Sulfur. The recommended choice for quenching this steel is in a luke warm oil, approx 200c (in the U.S Parks 50 is popular and in Australia Houghton’s K Quench oil seems to be the one to use). I can’t vouch for these but the following solutions have been known to be used for quenching:

- Many Different types of vegetable oils (Peanut, Canola, Palm, Soy bean, Corn, Sunflower, Rapeseed, Olive)

- Mineral Oils (Petro-Canada HLP Quench Oil, Chevron Quenching Oil 70R, Park Synthetic Heat Transfer Fluid, ExxonMobil Mobil Quench 70)

- Polymer/Synthetic Quenchants (Parks AAA Quench Oil, Houghto-Quench® 343, Super Quench® 44

- Engine Oil

- Animal Fats (…Really! I just thought htis was funny and worth a mention, although it’s more connected to blacksmithing back in the day)

- Water-Based Quenching Fluids (Straight Water, Brine Solutions)

- Air/Plate Quenching

Let’s take a closer look at them.

Vegetable Oils.

As you would expect these come from plants. Because the solutions are created by a bio degradable organic source they are becoming quite popular in the eyes of the environmental knife-maker, if there is such a thing! Actually they can produce good results with certain steels and they are less toxic. The quenching is slower compared to other mediums but all in all it’s not a bad choice.

Mineral Oils.

The use of these is quite common in certain areas of production. The big oil companies like Chevron & Exxon produce them. Personally I haven’t seen any knife-makers using this stuff so I suspect it’s for much larger operations in the big factories. They are very stable oils to use but they do have a much lower flashpoint than other oils so take care people if you use them at home, be careful how you use them, keep yourself safe.

Polymer/Synthetic Quenchants.

Being a synthetic product they are produced with particular steel in mind. D2 is often named in the heat treat process with this quenchant. It is quite stable and able to control the cooling rate compared to there solutions.

Engine Oil.

Engine oil is sometimes used for quenching knife blades. The viscosity of these old oil is pretty heavy, therefore it has a much more gradual cooling rate. 01 and D2 are tool steels you could quench in this oil. The question is, why would you do that? I guess if you are on the bones of your arse, then perhaps that’s what you need to do. It’s full of impurities and you won’t get a consistent quench.

Animal Fats.

Ha, wtf you might say. Quite a ways back in time blacksmiths used to use pig fat or the fat from around the kidneys of cows to quench tool and knife blades. The fat from around a cows kidneys is what we might associate in recent years as fat to fry fish and chips in…mm, lovely flavors, today apparently it’s unhealthy. Anyway, it’s not necessary to try quenching blades in anymore. The results are inconsistent as best. It’s quite flammable and stinks :0)

Water Based Quenchants.

Straight water. This has been used a lot in the past and continues to be used. There are many YT channels that use water and only water to quench their steel in. You need to be very careful using it though. It is very aggressive and only good for particular alloys. The most obvious one is W1, this is water hardening tool steel, perfect. On the other hand I have seen makers quenching all kinds of spring steel and alloys they have no idea what the steel elements are. They seem to achieve very good results.

Note: Makers using straight water often employ whats called an interrupted quenching process. This involves a technique of dipping the cutting edge in the water and taking it out and re-dipping it multiple times to slow down the process and reduce the stress and the likelihood of cracking the steel. It takes a bit of practice but can be quite effectively.

Air/Plate Quenching.

These are exactly as they are described. Air hardening steels are brought up to temperature and then cooled in still air and cool down at their own rate. A2 is a tool steel that is air hardening. If you can get the temperature right you can make yourself a nice little knife out of A2.

Plate quenching employs the use of two thick Ali plates (25mm or so) , as soon as the steel comes out of the forge it goes straight between these plates which suck the heat right out of it. A steel like AEB-L uses this technique. You might think so why bother with a high carbon steel and go through the messy, potentially flammable process with high carbon steel. One of the main reasons is you often need much higher temperatures to use this steel. Most home forges can’t do it.

What Actually Happens to the Steel During the Hardening Process?

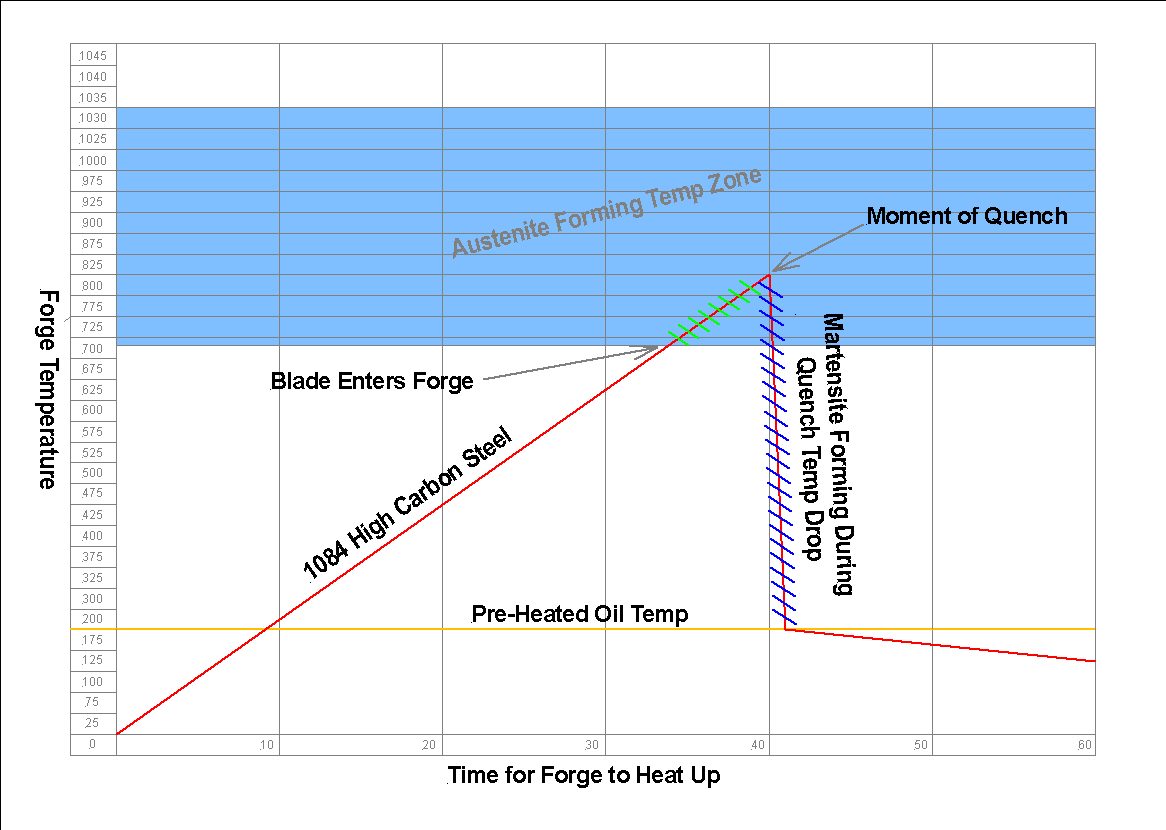

This little chart is a representation of a forge slowly heating up, actually it’s based on my own electric forge. It’s an example of how we heat treat 1084 high carbon steel. As the forge heats up to about 730c the steel begins to form Austenite. The blade goes in and quickly heats up to about 820c (I seem to get the best results at 820c). At this point the Quench takes place. This is where all the magic happens.

Body-Centred Tetragonal Crystal Structure

Body-Centred Tetragonal Crystal Structure

Nerd Alert: Sorry but this bit is very important to digest for anyone to fully understand what’s happening here. During the Austenite forming stage the steel, on a micro level, changes it’s crystal structure to what’s call face-centered cubic crystal. At this point the steel is non-magnetic which has a higher carbon solubility compared to it’s original state. Then comes the Quench where the rapid and from the steels perspective, quite violent cooling is done (I use Houghtons K Quench). This is where the steel changes from Austenite to Martensite. The martensite now has whats called a body-centered tetragonal crystal structure. The violent cooling process prevents the Carbon atoms from leaching out of the crystal structure which then leaves you with the hard brittle steel of Martensite. If you drop the steel on a hard surface at this point it might break or chip, it’s that hard.

So there you are, nerdiness over and now you know what happens to steel during the Quenching process.

Tempering.

Although this article is about ‘quenching’ the tempering process does need a mention. I will probably write an article dedicated tempering. For now though here is a brief overview.

The tempering process allows for the adjustment of the steel’s hardness while improving its toughness. It is a vital step to take out some of the brittleness created during the hardening process. Different tempering temperatures result in varying combinations of hardness and toughness, allowing manufacturers and the home knife-maker to meet the requirements of a particular type of steel and ultimately in the production of tools, machinery components, certain structural elements across different industries or the thing we love most and that’s Knives.

Conclusion

You can see how involved it can get to heat treat a knife. The thickness of the blade, the type of solution, the temperature, the quench time, the agitation in the tank and finally the tempering all make a difference to the end result. Your own forge may have a slight difference in the temperature reading compared to another forge. It really does take lots of practice to get it right and repeatable.

Now you can rush to your workshop and heat treat that blade you made sometime ago!

Hold your horses. This process has the potential to do some damage if you don’t take lots of care about what you are doing. The solutions can flash up like flame thrower and the workshop can get filled with smoke in no time. So do your research and watch a lot of YT videos. Wear your PPE, some kind of hard wearing face visor, mouth mask and goggles is a minimum. Have a fire extinguisher on hand, one appropriate for use on oils. Keep yourselves safe people.

As always, happy camping :0)